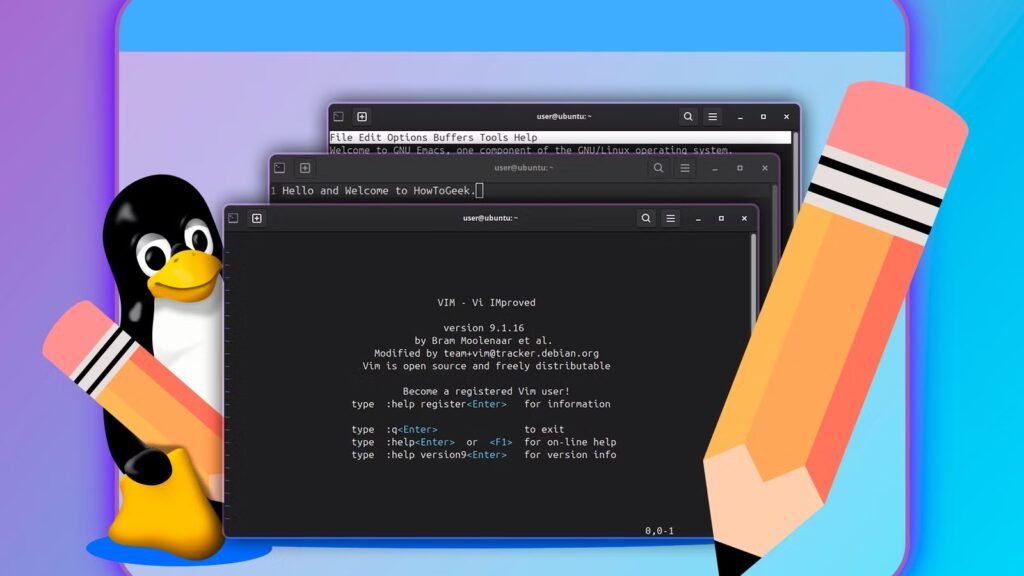

I used to shy away from buffers and tabs because the confusing terminology and obscure keyboard shortcuts put me off. But rest assured, learning all about buffers, windows, and tabs has transformed my Vim usage. I now wonder how I ever worked without them!

Getting started with buffers in Vim

First, try to think of a buffer as an open file. Vim lets you open several files at once, which means each gets its own buffer; you can switch between them, and you can display more than one at once.

You’re probably used to starting Vim like this:

vi filename

But, since Vim is perfectly happy opening more than one file at once, you can also run it like this:

vi foo bar hum

You can use shell expansion to open many files at once, e.g., vim *.md. I used to panic when I did this accidentally, but now I understand buffers, and I know it’s not a problem!

With multiple buffers open, you can show their names using the :buffers command:

Vim lists each buffer at the bottom of the screen, alongside a number to identify it and some additional information. The current (active) buffer is marked with a % symbol. You can also use :args to list buffers:

This command shows the filename arguments you passed to vi and encloses the current one in brackets. This is great for small numbers of files with short paths, but it can get pretty overwhelming otherwise!

The :args command will only show buffers that you created when starting Vim; it won’t show any files that you opened in buffers after that.

With several buffers open, you can edit and save files independently. For the most part, Vim works with buffers in the same way that you’d work with a single file, so you can still use :w to write the current buffer, :q to quit Vim, and so on.

For now, you’ll also need to know how to switch buffers. The easiest command is :bnext, which cycles to the next buffer, wrapping round at the end.

Instead of typing :bnext, you can use the abbreviation :bn. Like many other vi commands, these abbreviated versions can save a lot of time. If you see a command written like :bn[ext], you can use either the full version or its shorter abbreviation.

Advanced buffer techniques

Vim has many different buffer-related commands that you can use to refine your workflow. The built-in manual (:help) is an excellent source of information, if you’re comfortable navigating it. If not, this Vim cheat sheet is another great resource.

Many of these commands let you navigate buffers in different ways; for example, alongside the :bn command, there’s :bp[revious] and :b[uffer]#. The latter will switch to the buffer with number #, e.g., :b4.

The :b[uffer] filename command will switch to an open buffer with a matching name. You don’t have to use the exact filename if what you type is enough to unambiguously identify a single buffer, so :b fo will switch to the “foo” buffer in the above example.

Working with too many buffers can become unmanageable, but you can close one using the :bd[elete] command. Remember that :q[uit] closes vim, not just the active buffer.

If you switch buffers without saving, you’ll get an error message: “E37: No write since last change (add ! to override).” This is just a reminder that you need to save your work, but you can keep unsaved buffers open and hide this message in the future with the command :set hidden. Vim will still warn you if you try to quit without saving.

It’s possible to have no buffers open, for example, if you start Vim as vim -c ‘help | only’. This useful command opens Vim’s manual in a single window, but Vim doesn’t consider it a buffer.

Windows and tabs

Once you’re familiar with buffers, you can start thinking about how to display more than one at once, and how to group them. To be clear, you can use buffers without ever going near windows and tabs, much in the same way that you can run all apps maximized in your GUI. It’s all a matter of preference.

Vim windows let you split the screen and display more than one buffer at the same time. These pseudo-windows work a bit like a tiling window manager: they line up next to each other rather than overlapping. You can try the default horizontal split using the command :split:

This looks very confusing at first because Vim opens your existing buffer in the new window, leaving you with the same contents in both windows. It really is the same buffer and, before you continue, you can verify this by changing one of them:

OK, so this isn’t very useful with a small file, but you may find it useful when working on different parts of the same file. For now, you can open a different file in your current window using :e filename:

You can navigate between windows using two-key shortcuts that begin with Ctrl-w. For example, Ctrl-w w (hold Ctrl, press w, let go of both, then press w) will move to the lower window.

vim -o foo bar opens foo and bar in separate windows, split vertically.

Tabs are the top-level grouping that Vim offers; they are collections of windows. You can only view one tab at a time, but each tab may contain any number of windows.

The :tabe[dit] command opens a new tab and switches to it. When you’re using more than one tab, Vim will show a minimal tab bar at the top, with a name reflecting the buffer that’s currently active.

With tabs open, you can navigate between them using :tabn[ext] and :tabp[revious]. Close a tab using the :tabc command. Remember that closing a tab or window does not close the associated buffer; buffers can be detached and reattached as you see fit.

vim -p foo bar opens foo and bar in separate tabs.

Buffers, tabs, and windows are really powerful Vim features that many people overlook. Although there is much to learn beyond this article, once you start familiarizing yourself with these concepts, you should find that a much more productive editing experience has been waiting for you all along.