The first time Windows removed my Linux boot entry, it happened out of the blue; no crash, no warning, and no error message. All I had done was update Windows, and on startup, my computer booted straight into Windows. It was like Linux had never existed on the computer. All my partitions remained intact, but my firmware state didn’t.

Dual-booting is easy; however, these systems share a single EFI System Partition, modify UEFI boot variables, navigate TPM-backed security, and manage filesystems that don’t entirely trust each other. Treating it like a normal installation can be costly.

Not backing up and understanding the EFI System Partition

That small FAT32 partition decides what boots

Afam Onyimadu / MUO

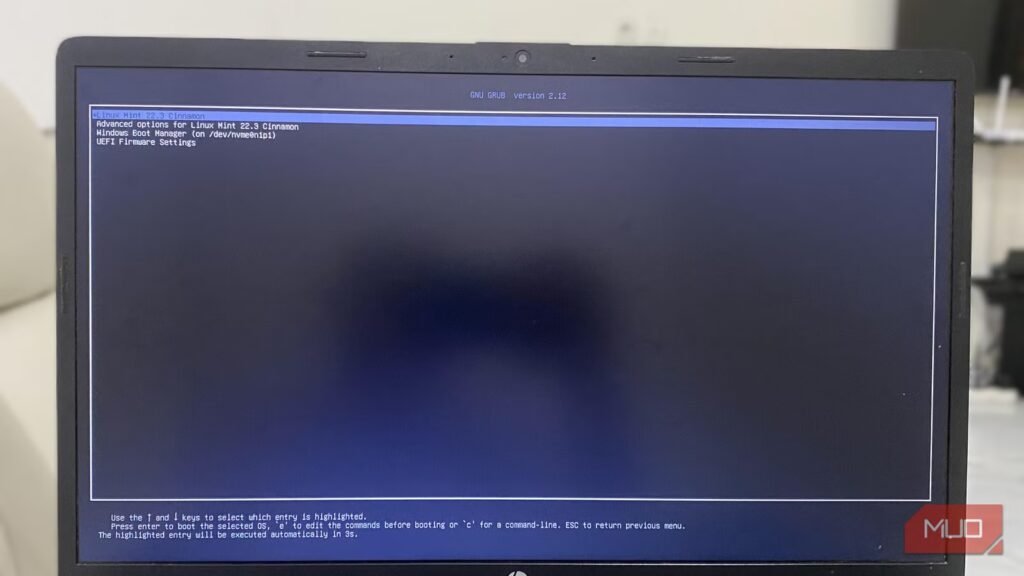

EFI System Partitions range between 100MB and 512MB and are typically formatted as FAT32 on modern computers. This appears as EFI System Partition on the Windows Disk Management tool, and Linux mounts it at /boot/efi. This partition includes the \EFI\Microsoft\Boot directory, and after installing Ubuntu, the \EFI\ubuntu directory. EFI System Partitions include Windows Boot Manager and GRUB’s EFI binaries; and the firmware first loads from this location before the OS starts.

However, in addition to the files in the ESP, your boot chain relies on correct partition identifiers because grub.cfg, which is GRUB’s configuration file, references the UUID (Universally Unique Identifier). The UUID matters a lot, especially if you clone disks, swap SSDs, or alter partition layouts. The ESP does more than act as a simple file container. It and UEFI NVRAM variables stored in firmware are integral parts of the boot ecosystem.

Attempting to fix a faulty multi-boot environment by reinstalling GRUB with a live USB and chroot is incomplete on its own. When your computer goes through a major recovery operation, in addition to overwriting ESP files, Windows also modifies firmware UEFI variables. This action will re-prioritize Windows Boot Manager, making it essential to verify boot order in BIOS/UEFI after a repair, since merely restoring files doesn’t restore firmware boot order.

My failsafe is backing up the ESP itself, twice: a Windows-only state, then a confirmed working dual-boot state. This is the workflow: back up, modify, back up again. The moment there’s a problem, I can use Clonezilla to restore the ESP image before confirming the boot order in firmware. It’s far more reliable and faster to restore a 100 to 512MB partition than to manually construct boot entries. As long as you dual-boot without ESP backups, the next disaster is always an update away.

Leaving BitLocker, Secure Boot, and TPM state unmanaged

Windows security assumes it controls the boot chain

Afam Onyimadu / MUO

Windows 11 typically enables BitLocker by default on new, pre-built systems, especially those that have TPM 2.0, a security chip on the computer’s motherboard. The BitLocker feature ties disk decryption to bootloader integrity and firmware configuration, which are two measured boot components. The operating system assumes there’s been tampering when any of the measurements change, at which point the TPM will refuse to release the Volume Master Key.

However, while you can choose between suspending and disabling BitLocker, the two are critically different. Suspension is temporary and doesn’t decrypt the drive or remove its connection to the TPM. Turning it off, on the other hand, is a full decryption process and the better option if you need to resize partitions or modify the boot configuration. You can run the command below to verify the status of BitLocker on Windows:

manage-bde -status

Disable BitLocker by running this command: manage-bde -off C:

The other layer to consider is Secure Boot. Some big distros like Ubuntu, OpenSUSE, and Fedora have signed bootloaders and can support Secure Boot. However, some other distros don’t have a signed bootloader and may fail under Secure Boot. You can’t guarantee how your primary recovery tool will behave with Secure Boot enabled. I disabled it before installation. This isn’t to say Linux can’t work with it, but that it makes recovery unpredictable.

The real TPM complications arise from drive swaps. On some machines where I replaced SSDs, I watched Windows invalidate the previous boot context. This forces password authentication and rewrites the boot priority. So, even though Linux wasn’t wiped, it stopped being the first in line. Avoid toggling TPM, Secure Boot, or firmware security settings once both OSes are installed, because these aren’t neutral actions. Freezing the security settings after both OSes are installed is essential for stability.

Assuming Windows won’t rewrite your bootloader

Feature updates and recovery reset UEFI priorities

Windows version upgrades create a problem. The process typically resets your device’s UEFI boot entries. While the update leaves GRUB untouched, Windows doesn’t prioritize GRUB in firmware NVRAM. This creates the impression that Linux has been erased.

Windows Recovery can be even more destructive because it rebuilds the boot configuration data inside the ESP, and Linux EFI entries are overwritten. A partition containing Linux may be intact, but the firmware may still be unable to point to it. While the data is preserved, the boot path is destroyed.

I generally disable Fast Startup on my computer. One problem is that it sets firmware flags to perform a hybrid boot after writing the Windows kernel to a hibernation file. Because the process can bypass the normal boot menu presentation, it appears as if the system has skipped GRUB.

You may not be able to permanently defend against Windows re-prioritizing itself after a major update. Any defense you put in place must be procedural: keep a current ESP backup, verify boot order after feature upgrades, and expect occasional interference. The only way to make dual-booting predictable is by assuming Windows wouldn’t preserve your shared boot infrastructure.

Treating partitions and shared filesystems casually

NTFS resizing and cross-OS storage require discipline

Afam Onyimadu / MUO

Shrinking Windows safely is non-negotiable, which implies that you can’t resize NTFS if it’s not in a clean state. The Fast Startup feature is enabled by default and typically leaves NTFS in a semi-hibernated state, increasing the risk of corruption. You should disable Fast Startup, disable hibernation, and fully decrypt BitLocker; only then can you safely shrink the partition using Windows Disk Management. I always run the chkdsk tool afterward just to confirm integrity.

Windows has four partitions, and you should pay attention:

- EFI System Partition (FAT32)

- Microsoft Reserved Partition (hidden, about 16MB)

- Windows C: (NTFS)

- Sometimes, a Windows Recovery partition

You can see the Microsoft Reserved partition on Linux tools, but it’s hidden on Windows. So technically, you can delete it. However, if you don’t perfectly understand Windows disk management, deleting it can be a huge mistake because it’s integral to some disk operations and handles metadata.

In recovery processes, Windows will likely treat ext4 or Btrfs as unallocated because it doesn’t understand them. The pragmatic choice for shared data is NTFS. However, if Windows shuts down and Linux mounts that NTFS partition read-write, corruption can occur. The ideal is to perform a real shutdown before booting into Linux; no Fast Startup.

Where dual-boot fails

When dual-boot fails, it does so at firmware boundaries, encryption boundaries, and filesystem boundaries. You must take extra precautions at these points. You’ll avoid disaster if you back up the ESP, freeze the firmware security state, expect Windows to reset the boot order, and handle NTFS properly.

Related

10 Practical Uses for a USB Flash Drive You Didn’t Know About

You’ve used USB sticks to transport files between computers and back up files, but there is much more you can do with a USB stick.